Cesar Tarrant: Patriot Pilot

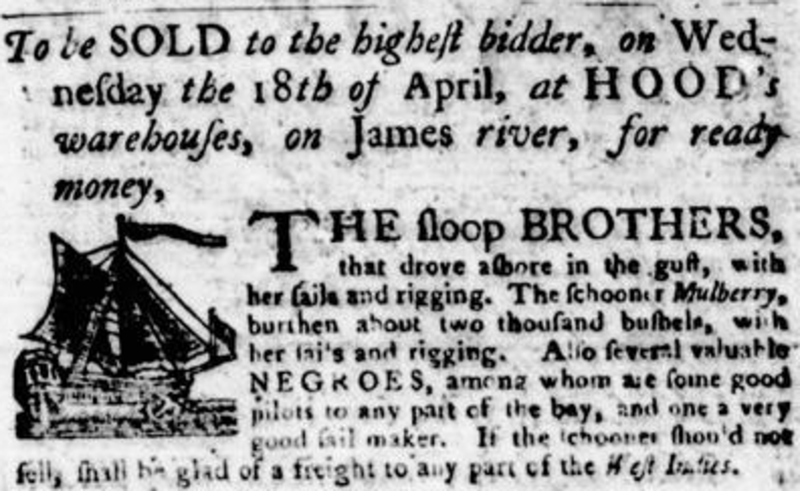

Enslaved mariners plied Virginia’s many waterways to bring tobacco and other goods to market and back. The Virginia Gazette is packed with references to enslaved sailors, pilots, and even captains in the 1770s. Often called “skippers,” enslaved ship captains such as Minny, once owned by Joseph Pritchard of Urbanna, were “well acquainted with the bay, and all the rivers in Virginia and Maryland.” Williamsburg’s Robert Carter III owned an enslaved skipper named William Lawrence who regularly sailed the schooner Harriot between Richmond and Norfolk. Enslaved mariners frequently found themselves in positions of great trust and responsibility, working out of sight of their enslavers.

Maritime skills were in high demand in Revolutionary Virginia. Knowing how to navigate waterways could also occasionally offer an enslaved person a chance at freedom. In a proclamation dated 14 November 1775, Virginia’s last royal governor, Lord Dunmore, offered freedom to all enslaved people who were able and willing to bear Arms.” Aided by several small Royal Navy vessels, loyalist Virginians, and eventually some 800 Africans hoping to escape enslavement, Dunmore spent the next several months ravaging rebel plantations and settlements within easy striking distance from Virginia’s creeks and rivers. These raids led the Virginia Convention to call on 23 December for local Committees of Safety to acquire and deploy “so many armed vessels as they judge necessary” to protect Virginia by water. At least fifty vessels served in the Virginia Navy during the American Revolution, crewed by approximately 1,700 men, of which at least 140 were of African descent.

Advertisement from Purdie and Dixon’s Virginia Gazette dated 5 April 1770.

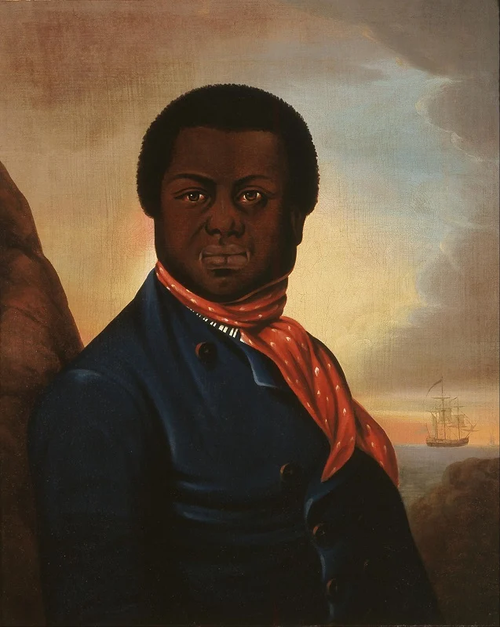

One of the earliest vessels brought into the Virginia Navy was the schooner Patriot, a pilot boat modified to carry ten small swivel guns and twenty men. Among Patriot’s crew was Cesar, an enslaved man owned by Carter Tarrant of Hampton. Born around 1740, Cesar was trained as a river pilot, responsible for guiding vessels to safe moorings in local waters. With the outbreak of the American Revolution, Cesar was one of seven pilots (four of whom were enslaved) appointed by the Virginia Navy Board. He entered the service in 1776 or 1777 and continued there after the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781.

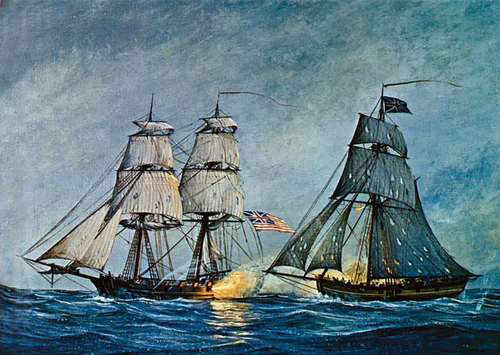

In October 1778, Patriot was sailing in company with the Virginia Navy ships Dragon and Tartar under the overall command of Captain Richard Taylor. When the British privateer Lord Howe entered the Chesapeake Bay, Dragon attempted to lure the enemy closer by masquerading as a merchantman. Only Patriot was quick enough to pursue when Lord Howe saw through the ruse and attempted to flee.

Despite facing a larger and more heavily armed vessel, Captain Taylor ordered Patriot to ram Lord Howe, hoping to board and capture her. The British vessel fired a broadside that raked Patriot fore and aft, killing two Virginians and seriously wounding several others. When Dragon was eventually able to get close enough to join the fight, Lord Howe’s crew threw their cannon overboard to hasten their escape. Owing to his tenacity in battle, a correspondent to the Virginia Gazette voiced the hope that American historians would rank Captain Taylor alongside British naval heroes of the day. Cesar had been in the thick of things as well: not only did Captain Taylor praise the pilot’s performance in combat, but years later Patriot’s gunner, James Burk, testified that Cesar had “steered the Patriot during the whole of the action, and behaved gallantly.”

Even after the 1783 ratification of the Treaty of Paris secured American independence, Cesar remained enslaved by the Tarrant family. How and why Cesar came to fight for Virginia remains unknown, but it was apparently not as a substitute for his master. An act of the Virginia General Assembly dated 20 October 1783 declared that all enslaved persons who had served as substitutes in the American forces during the Revolution were to be emancipated. Only after another six years had passed did the General Assembly acknowledge that Cesar had “entered very early into the service of his country, and continued to pilot the armed vessels of this state during the late war; in consideration of which meritorious services it is judged expedient to purchase the freedom of the said Cesar.”1 While Cesar became a free man, his wife Lucy and their three children (Sampson, Lydia, and Nancy) remained enslaved in Hampton and Norfolk.

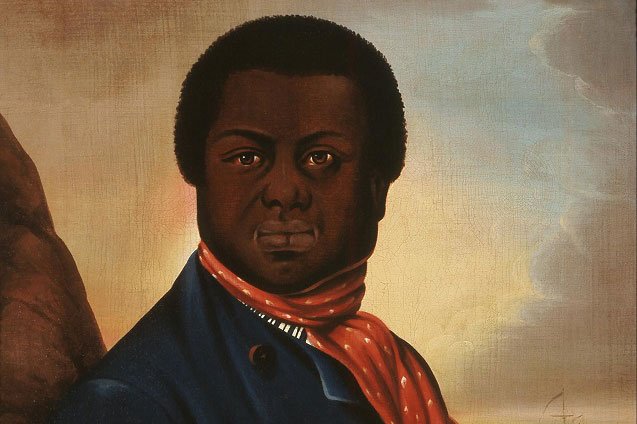

“Portrait of a Black Sailor” by Paul Cuffe, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Cesar continued working as a local pilot, eventually taking the surname Tarrant and purchasing his own land in Hampton. Cesar and other pilots of color were apparently respected enough by their white colleagues that petitioners convinced the Virginia legislature to allow African -American pilots to be officially licensed in the same manner as whites. The following year, Cesar purchased the freedom of his wife and ten-month-old daughter Nancy. He died in 1797 before he could see his other children emancipated. Little is known of Sampson, who likely died enslaved.

Twenty-five years after Cesar’s death, Lucy was able to purchase the freedom of Lydia, who regrettably had to leave a child of her own in bondage. In 1831, with supporting testimony from Virginia Navy veterans James Burk and William Jennings, Nancy successfully petitioned the Virginia legislature for a grant of over 2,600 acres of land on the frontier owed to her father for his Revolutionary War service. Through the sale of that land, Nancy purchased the freedom of her husband James and two other relatives. While the wheels of emancipation turned slowly, once hopes that Cesar would be comforted by the fact that his own wartime service led directly to the freedom of at least six members of his family.

Little known outside of Hampton (where Cesar Tarrant Middle School is named in his honor) Cesar’s is one of many overlooked chapters in America’s enduring story.

Resources

- “An act for the purchase and manumitting negro Caesar,” in William Waller Hening, ed., (Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, 1823), 102, link.

Further Reading

- Bilal, Kolby. “Black Pilots, Patriots, and Pirates: African-American Participation in the Virginia State and British Navies During the Revolutionary War in Virginia”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2000.

- Bolster, W. Jeffrey. Black Jacks: African-American Seamen in the Age of Sail. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Eve - Lord Dunmore's Proclamation. Museum of the American Revolution. https://www.amrevmuseum.org/virtualexhibits/finding-freedom/pages/eve-lord-dunmore-s-proclamation.

- Hays, Alex. “America’s First Black Sailors.” The Sextant. Naval History and Heritage Command. https://ussnautilus.org/americas-first-black-sailors-2/

- Long, Charles Thomas. "Green Water Revolution: The War for American Independence on the Waters of the Southern Chesapeake Theater." PhD diss., The George Washington University, 2005.

- Stewart, Robert Armistead. The History of Virginia's Navy of the Revolution. Richmond: Mitchell & Hotchkiss, 1934.